꩜ Origins & Historical Roots

Integral Theory was born out of a very specific cultural moment. The late twentieth century saw the West grappling with fragmentation on every front: psychology split into competing schools, religion was losing its grip in the face of secularism, science was accelerating without providing meaning, and postmodern philosophy had dismantled grand narratives until little seemed to hold. Into this chaos stepped Ken Wilber, a young autodidact with an encyclopedic appetite for philosophy, spirituality, and science. Beginning in the late 1970s, Wilber published a series of works that attempted something audacious: to gather the scattered fragments of human knowledge—Eastern and Western, ancient and modern—and weave them into one coherent picture. His aim was nothing less than a “theory of everything,” a single framework capable of situating every perspective and practice without dismissing any of them.

Wilber’s early writings were deeply influenced by transpersonal psychology, a field that had emerged in the 1960s to study spiritual experience through the lens of psychology. Figures like Abraham Maslow and Stanislav Grof had already begun breaking the boundaries of conventional psychology by exploring peak experiences, altered states, and mystical consciousness. Wilber took this groundwork and pushed it further, integrating developmental psychology with Eastern mysticism. He drew on Jean Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, Lawrence Kohlberg’s stages of moral reasoning, and Clare Graves’s emergent cyclical model of values—psychological theories that charted how individuals grow through predictable stages. To these, he added Buddhist and Vedantic models of enlightenment, which claimed that consciousness itself could evolve into transpersonal, non-dual awareness. The result was a scaffolding that blended Western developmental science with Eastern spiritual hierarchies.

From the start, Wilber positioned himself as both a synthesizer and a critic. He argued that most traditions, whether scientific, religious, or psychological, were partial truths masquerading as wholes. Science reduced everything to matter. Religion reduced everything to faith. Psychology reduced everything to the psyche. Each had a piece of the puzzle but mistook it for the entire picture. His solution was what he would later call “Integral”: a framework that would honor the truth in every domain while exposing its limits. No perspective would be dismissed, but none would be allowed to dominate. In this sense, his project was radically inclusive but also ruthlessly systematic.

The intellectual climate of the 1980s and 1990s provided fertile ground. Systems theory was on the rise, emphasizing interconnection and holism. Postmodern philosophy had deconstructed absolutes but offered little constructive vision in their place. New Age spirituality was exploding, often drowning in vagueness. Wilber’s work appealed to those who wanted depth without dogma, structure without rigidity. His books—The Spectrum of Consciousness (1977), The Atman Project (1980), Sex, Ecology, Spirituality (1995)—established him as a singular figure who could write with equal fluency about quantum physics, tantric yoga, and developmental psychology. By the mid-1990s, he had crystallized his approach into what became known as the AQAL model, a formal structure that would define Integral Theory.

It is important to see that Integral Theory did not descend as revelation but was assembled, brick by brick, out of existing traditions. Wilber borrowed freely, sometimes acknowledging sources, sometimes rebranding them into his own terminology. The genius of his project lay not in discovering something wholly new, but in connecting what was already known into a single architecture. He gave scattered insights a home. Whether one agreed with his system or not, it was impossible to deny the scope of his ambition: in a time of disintegration, he attempted reintegration. That drive—to unify the fragments of human understanding—remains the heartbeat of Integral Theory, and the reason it continues to attract both admiration and critique.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Core Structure of the Model

At the heart of Integral Theory lies the AQAL framework—an acronym that stands for “All Quadrants, All Levels.” This is Wilber’s attempt to capture the totality of reality in a single schema, a grid spacious enough to contain science and mysticism, psychology and sociology, meditation and economics, without collapsing them into one another. AQAL was not meant as a metaphor but as a literal cartography of existence: every phenomenon, whether a thought, a culture, a cell, or a galaxy, could be located within its coordinates. Where earlier systems leaned on myth, symbol, or intuition, Wilber sought to present a formal architecture that could withstand philosophical scrutiny. AQAL was to be the grammar of reality itself.

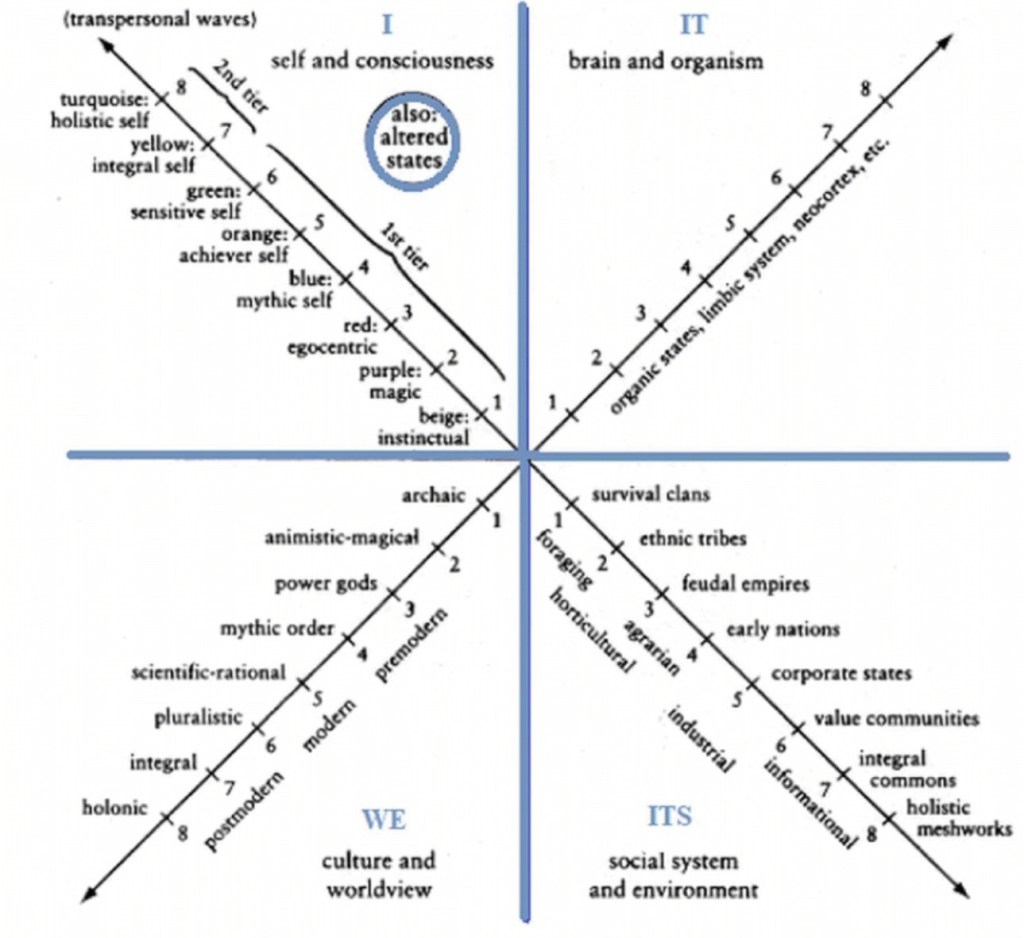

Ken Wilber’s Integral Model (AQAL) — the foundational four-quadrant map uniting subjective, intersubjective, objective, and interobjective perspectives. Public-domain educational diagram.

The first axis is the quadrants, which divide experience into four irreducible perspectives. On one side lies the distinction between the interior and the exterior; on the other, the difference between the individual and the collective. Taken together, these yield four quadrants: the interior-individual (the subjective realm of thoughts, feelings, and intentions), the exterior-individual (the objective realm of behavior, biology, and matter), the interior-collective (the intersubjective domain of culture, language, and shared meaning), and the exterior-collective (the interobjective realm of systems, institutions, and ecological networks). Wilber insisted that no perspective can be reduced to another. Neuroscience can map brain activity (exterior-individual) but cannot explain the lived feeling of joy or despair (interior-individual). Sociology can analyze institutions (exterior-collective) but cannot capture the spirit of culture (interior-collective). To ignore any quadrant is to distort reality.

The second axis is levels, the developmental stages through which individuals and societies grow. Drawing on psychology, anthropology, and spirituality, Wilber argued that consciousness unfolds in predictable waves: from prepersonal instincts to personal rationality to transpersonal awareness. Each stage transcends and includes the previous, forming a spiral of increasing complexity and depth. Moral reasoning, cognitive ability, self-identity—all move through these levels. For Wilber, this evolutionary trajectory was not an optional theory but a law of development, as universal as gravity. It explained why children grow through distinct phases of thought, why cultures evolve from tribal to industrial to global, and why mystics describe higher states of awareness. The ladder of levels gave Integral Theory its sense of direction, its narrative of progress.

Yet Wilber recognized that development is not singular. He introduced the concept of lines—multiple intelligences that evolve semi-independently. A person might be highly advanced in cognitive skill but stunted in emotional or moral growth. Another might excel in aesthetic intuition but lag in interpersonal sensitivity. By distinguishing lines, Wilber accounted for unevenness, explaining why geniuses can be ethically blind or why spiritual teachers may collapse in scandal. Growth, in this model, is plural: one must attend to many lines of development, not just a single measure of “enlightenment.”

The fourth element is states, the temporary modes of consciousness available to all humans regardless of their developmental level. Dreaming, deep sleep, waking awareness—these are universal states, but so too are meditative absorption, visionary rapture, or psychedelic trance. States offer windows into higher realities, even if one has not stabilized them through development. Wilber integrated states into the model to explain why a beginner might glimpse unity in meditation but lack the maturity to embody it. Stages are earned over time, but states can be tasted at any point.

Finally, Wilber added types, a flexible category for differences that cut across quadrants, levels, lines, and states. Masculine and feminine polarities, personality typologies like the enneagram or Myers-Briggs, even astrological archetypes—all find a place here. Types remind the model that not all variation is developmental; some are structural, inherent differences in how consciousness manifests.

Together, these five dimensions—quadrants, levels, lines, states, and types—compose the AQAL system. Wilber presented it as a meta-framework, not another partial theory but the skeleton that could hold every other map. A meditation technique, a laboratory experiment, a cultural ritual, a social policy—each could be located within AQAL, ensuring that no dimension of truth was dismissed. For Wilber, this was the safeguard against reductionism, the guarantee that science, art, morality, and spirituality would all be honored as valid perspectives. AQAL’s ambition was nothing less than inclusivity without collapse, differentiation without fragmentation.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Functional Role of the Framework

AQAL was meant to be used as a lens through which all knowledge and experience could be clarified, positioned, and integrated. The framework does not simply describe reality—it organizes it. Its role is to prevent reductionism, to remind us that no single perspective tells the whole story, and to offer a coherent way of navigating complexity without dissolving into chaos. In short, its function is orientation.

The quadrants, for example, function as a check against blind spots. If a researcher claims depression is “just” brain chemistry, AQAL forces the reminder that interior experience (subjective anguish), cultural context (stigma, language, narratives), and social systems (economic pressures, healthcare access) are equally real dimensions. If a mystic insists that enlightenment is the only truth, AQAL insists that biology, culture, and institutions also matter. Each quadrant ensures that partial truths are contextualized rather than absolutized. The framework operates like a compass: if you drift too far into one direction, it reminds you of the other three.

The levels function as a developmental roadmap. They situate individuals and cultures within an evolutionary trajectory, offering a way to interpret differences without collapsing into relativism. A child’s moral reasoning is not the same as an adult’s; a tribal worldview is not the same as a global one. By framing these as stages, Wilber gave meaning to diversity: every perspective is valid at its own level but limited by it. The role of levels is to orient growth, to show that consciousness has direction. This prevents both the arrogance of assuming one’s stage is the final stage and the nihilism of believing all stages are equal.

The lines function as diagnostics. By distinguishing cognitive, emotional, moral, spiritual, and aesthetic lines of development, AQAL explains the unevenness of human maturity. A brilliant scientist may collapse morally; a compassionate teacher may lack intellectual clarity. The role of lines is to reveal where growth is strong and where it is weak, providing a map for practice. Without them, development looks deceptively smooth; with them, the rough edges of human complexity are accounted for.

The states function as windows. They remind us that temporary experiences of unity, ecstasy, or altered consciousness are available to all, regardless of stage. Their role is twofold: to validate mystical reports as part of human potential, and to caution against confusing fleeting glimpses with permanent attainment. A novice can taste non-duality in meditation, but only sustained development stabilizes it. In this way, states function as both invitation and warning: they offer inspiration, but they also demand integration.

The types function as a balancing factor. They recognize that not all differences are hierarchical. Masculine and feminine tendencies, introversion and extraversion, typological archetypes—these cut across levels and quadrants, shaping how individuals manifest their growth. Their role is to prevent the flattening of diversity into a single spectrum. Not every variation is developmental; some are structural expressions of consciousness itself.

Taken together, these functions transform AQAL into a practical toolkit. It allows therapists to situate their work within both subjective and cultural contexts. It enables organizational leaders to see that structures, values, and individual psychologies all matter. It provides spiritual practitioners with a framework to integrate meditation, shadow work, and cultural critique. Above all, its function is integration: to weave the fragments of knowledge into a tapestry that honors each thread without reducing it to the others.

In this sense, Integral Theory is less about answering “what is true?” than about ensuring that every truth has a place. Its function is to prevent the arrogance of partiality, to insist that reality is multi-faceted, and to offer a meta-structure that allows complexity to be held without collapse. Whether one accepts its universality or not, the functional role of AQAL is undeniable: it provides a way to think, act, and grow that refuses to leave any perspective behind.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Human Interaction with Integral Theory

Integral Theory presents itself as a map of everything, but its value is only proven when it is lived. For Wilber and his followers, the model is not an armchair philosophy but a practical framework through which people can navigate therapy, meditation, relationships, organizations, and even politics. The claim is that AQAL is not merely descriptive but operative—that by applying it, we interact differently with ourselves and the world. To use Integral Theory is to change perspective.

In personal growth, the model serves as a mirror. A practitioner might use it to track which developmental lines are thriving and which are stunted. A person might recognize that cognitively they are advanced—capable of abstract thought and complex reasoning—yet emotionally they are immature, still repeating adolescent patterns. By naming these gaps, the model offers direction for practice: meditation may deepen state access, but shadow work may be necessary to integrate the emotional line; education might sharpen cognition, but relationships are where empathy develops. Human beings interact with the framework by using it diagnostically, a kind of multi-dimensional check-in that prevents one-sided growth.

In therapy and psychology, Integral Theory provides a broad lens that prevents reductionism. A therapist influenced by AQAL might examine a client’s depression across all four quadrants: the subjective despair of the interior, the biological imbalances of the exterior, the cultural narratives of shame in the intersubjective, and the systemic pressures of economy or family in the interobjective. Each is real, and each demands attention. The interaction here is not just theoretical—it reshapes how problems are defined and how solutions are designed. Depression is not “just” brain chemistry or “just” negative thinking; it is a multi-plane phenomenon. AQAL reframes healing as an integrative process across perspectives.

In spiritual practice, Integral Theory operates as both a validator and a safeguard. States of mystical absorption, for instance, are legitimized as genuine dimensions of consciousness, not dismissed as hallucinations. But the framework also warns against inflation: a momentary state is not equivalent to developmental stabilization. Practitioners interact with AQAL by using it to interpret their experiences, to place their meditation, prayer, or psychedelic journeys within a larger structure that distinguishes fleeting glimpses from enduring growth. This interaction tempers both doubt and hubris—recognizing the validity of extraordinary experiences while reminding practitioners that embodiment and integration are the true tests.

Beyond individuals, organizations and education have adopted Integral Theory as a design tool. Educators use it to frame curricula that balance cognitive, emotional, moral, and spiritual development. Leaders use it to analyze institutions, mapping how values (interior-collective) interact with systems (exterior-collective), and how both shape individual behavior. Here the interaction is systemic: AQAL is used to diagnose organizational blind spots, to ensure that policy and culture are not treated as separable silos but as interdependent realities.

Even in social and political analysis, Integral Theory provides a lens for interaction. Wilber and his followers have used it to argue that cultural conflicts are often clashes between developmental stages—traditionalist vs. modernist vs. postmodernist worldviews—each valid in its context but limited when absolutized. Interacting with the model here means learning to engage difference not as a battle of right vs. wrong but as a negotiation between developmental perspectives. The framework does not eliminate conflict, but it re-situates it in a broader evolutionary arc.

In all of these examples, human interaction with Integral Theory boils down to one function: orientation toward wholeness. The model is used to track where growth is occurring, where it is blocked, and how different dimensions intersect. It reshapes therapy into a multi-perspective practice, spirituality into a developmental journey, leadership into a systemic integration, and social conflict into an evolutionary dialogue. To interact with AQAL is to be reminded constantly that reality is layered, that perspectives are plural, and that any single truth is partial.

For this reason, those who adopt Integral Theory often describe it less as a philosophy and more as a practice lens—a way of seeing that once absorbed cannot be easily set aside. To live integrally is to filter every experience through quadrants, levels, lines, states, and types. Whether this is clarity or obsession depends on the practitioner, but the interaction itself is unavoidable once the framework has been internalized.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Purpose and Esoteric Function

Integral Theory did not emerge as a neutral academic project. From its inception, it carried the weight of purpose. For Ken Wilber, AQAL was not merely a descriptive grid but a prescriptive path, a way to point humanity toward its evolutionary destiny. Where Theosophy cast the seven planes as a ladder of spiritual ascent, Integral Theory reframed development in psychological and cultural terms: individuals, societies, and civilizations must evolve through stages of consciousness if they are to survive. The model thus functions not only as a map of what is, but as a mandate for what must be.

The central purpose of the framework is integration. Wilber believed the crises of the modern world—ecological collapse, cultural fragmentation, political polarization—stem from partial perspectives absolutized at the expense of the whole. Science reduces life to mechanism, religion reduces it to faith, postmodernism reduces it to relativism. Each is partly true, but each becomes dangerous when mistaken for the whole. The esoteric function of AQAL is to prevent this collapse into one-sidedness, to hold all perspectives together without erasure. Its purpose is to teach humanity to think integrally, to refuse reductionism, and thereby to heal the fractures of modernity.

At the individual level, the function is developmental awakening. Wilber framed human growth as a journey through successive waves: from egocentric to ethnocentric to worldcentric to kosmocentric awareness. The purpose of life, in this schema, is to transcend narrow identities and embrace wider circles of care. The esoteric implication is clear: enlightenment is not simply private mystical union but the expansion of consciousness into inclusive embrace. AQAL functions as a spiritual scaffolding, guiding seekers from personal shadow work to transpersonal realization, while insisting that each step must be integrated rather than bypassed.

At the cultural level, the purpose is evolutionary survival. Wilber warned that humanity stands at a precipice: if it fails to evolve into what he called “second-tier consciousness”—the capacity to integrate all perspectives—civilization may collapse under its own fragmentation. Modernity gave us science but dismissed spirituality; postmodernity gave us critique but dismissed structure. Only an integral vision, he argued, could reconcile these partial truths into a coherent global order. The framework thus takes on the tone of prophecy: evolve or perish. In this sense, its esoteric function mirrors religious soteriology, promising salvation not through grace or ritual but through developmental integration.

Beyond practical and cultural aims, Integral Theory also carries a metaphysical purpose. Wilber consistently drew on Eastern non-dual traditions, particularly Buddhism and Vedanta, to argue that the ultimate aim of consciousness is realization of Spirit as both emptiness and form. The AQAL framework, for all its psychological and sociological sophistication, is oriented toward this esoteric climax: the recognition that the quadrants, levels, lines, states, and types are all manifestations of the same underlying Spirit. Its hidden function, then, is mystical. It is not just a grid of knowledge but a ladder toward awakening.

In sum, the purpose of Integral Theory is twofold: to serve as a practical operating system for modern complexity, and to act as a spiritual blueprint for human evolution. Its esoteric function is to re-enchant the world without abandoning rationality, to legitimate spirituality without dismissing science, and to provide humanity with a story big enough to hold its fragments. Whether one accepts this purpose as visionary or overreaching, there is no denying the ambition.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Criticisms and Limits

Integral Theory dazzles with its scope, but the very breadth that makes it attractive also opens it to criticism. At its core, AQAL is both brilliant synthesis and overreach. To honor the system fully, one must also confront its limits.

The first critique is over-systematization. Wilber’s framework, like Theosophy’s ladder before it, runs the risk of mistaking neat diagrams for living reality. By insisting that every phenomenon can be placed into quadrants, levels, lines, states, or types, Integral Theory sometimes forces complexity into boxes that do not fit. Consciousness is not always linear; cultures do not always evolve in predictable sequences. Mystical states can collapse hierarchies rather than climb them. Yet AQAL’s elegance tempts adherents to assume it is exhaustive, a map that leaves nothing out. The result is a model that feels totalizing—orderly, but at times reductionist in its very attempt to prevent reductionism.

A second criticism is intellectual elitism. Wilber’s writings are famously dense, peppered with jargon that demands extensive background knowledge. While he sought to make Integral Theory a universal framework, the barrier to entry is high. Critics argue that this elitism undercuts the very inclusivity the model claims to champion. Integral discourse often circles among academics, spiritual leaders, and high-level practitioners, leaving the average seeker or layperson overwhelmed. The irony is sharp: a theory meant to embrace all perspectives risks becoming the property of a narrow intellectual class.

A third limit is Wilber’s dominance over the system. Integral Theory is so closely tied to its founder that it sometimes feels less like an open framework and more like a personal empire. While Wilber drew from countless sources, the branding, terminology, and authority all point back to him. This raises questions of pluralism: is Integral Theory truly a space for all perspectives, or a single man’s synthesis presented as universal? The model’s reliance on Wilber’s voice has limited its growth into a broader intellectual movement, keeping it tethered to his authority rather than opening into collective authorship.

The fourth critique is empirical weakness. Much of the developmental psychology Wilber leaned on—stage theories from Piaget, Kohlberg, and Graves—has faced heavy revision or critique. Cultural evolution is not as tidy as spiral models suggest; moral development does not always follow linear stages; individual growth can regress, fragment, or skip. While AQAL presents development as a universal law, empirical psychology is far more ambivalent. This gap leaves the framework vulnerable: it looks scientific, but its scientific grounding is uneven.

A fifth limit is spiritual bias. Despite its claim to include all perspectives, Integral Theory privileges a very particular trajectory—one rooted in Eastern non-dualism. The end point of development is consistently framed in Buddhist and Vedantic terms: realization of emptiness, recognition of Spirit, transcendence of duality. While this may resonate with Wilber’s personal path, it raises questions about cultural bias. Indigenous cyclical cosmologies, Christian relational mysticism, or animist worldviews fit awkwardly within AQAL’s hierarchy. The “integration” it promises is thus selective, weighted toward certain traditions while sidelining others.

Finally, critics point to practical dilution. Because Integral Theory tries to include everything, it risks becoming too abstract to act on. Leaders, therapists, and practitioners may admire the grid, but translating it into concrete practice can be difficult. The danger is that AQAL functions more as a grand intellectual edifice than as a transformative tool. Its comprehensiveness can paralyze as much as it clarifies, overwhelming with categories rather than guiding with simplicity.

None of these critiques erase the value of Integral Theory. It remains a bold attempt to unify fragmented knowledge, and its framework has inspired real practice in psychology, education, spirituality, and organizational design. But its limits are clear: it is a system built by one mind in a specific cultural moment, not a final revelation of reality. Its elegance conceals its fragility. To use AQAL wisely is to treat it as one powerful lens among many, not as the master key it sometimes claims to be.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Cross-Mapping to Other Systems

Integral Theory did not emerge in isolation. Wilber’s framework is best understood as a deliberate convergence point where older systems were gathered, reinterpreted, and slotted into a single architecture. Looking at these cross-mappings exposes both the depth of his synthesis and the cultural biases baked into it.

The most direct parallel is with Theosophy’s seven planes of existence. Both models imagine reality as layered, developmental, and hierarchical, with human beings stretched across multiple levels of embodiment and awareness. Theosophy divided existence into dense, emotional, mental, intuitive, volitional, and divine planes; Wilber reframed this ladder as prepersonal, personal, and transpersonal stages. The resonance is clear: both claim that evolution proceeds from matter to spirit, from fragmentation to unity. But where Theosophy leaned on clairvoyant reports and esoteric tradition, Wilber leaned on developmental psychology and non-dual philosophy. The scaffolding is similar; the justification is different.

Wilber also explicitly absorbed Spiral Dynamics, a model developed by Clare Graves and popularized by Don Beck and Chris Cowan. Spiral Dynamics describes human values evolving through color-coded stages, from survivalist beige to egocentric red, traditional blue, rational orange, pluralistic green, and beyond. Wilber folded this directly into Integral Theory, situating it as one example of the “levels” dimension. Where Spiral Dynamics focuses on cultural values, Wilber expanded the frame to include cognition, morality, spirituality, and beyond. Yet the inheritance is clear: Integral Theory’s developmental arc is inseparable from Graves’s original insight that values evolve in predictable waves.

The Eastern traditions are even more central. Wilber drew heavily on Buddhism, particularly Mahayana and Vajrayana, for his account of meditation, states, and ultimate realization. The Buddhist ladder of meditative absorption, the recognition of emptiness, and the emphasis on non-dual awareness all saturate Integral Theory’s higher stages. From Vedanta, he borrowed the Atman-Brahman identity, the spectrum of consciousness from waking to deep sleep to turiya (the fourth state), and the goal of realizing Spirit as both form and emptiness. These were not peripheral influences—they shaped his vision of what “full development” meant. Critics argue that this gives Integral Theory a distinctly Eastern flavor, even as it claims to be universal.

From the Western esoteric tradition, echoes of Neoplatonism and the Great Chain of Being are evident. Plotinus’s triad of One, Intellect, and Soul maps onto Wilber’s spectrum of gross, subtle, and causal consciousness. Hermeticism’s principle of correspondence—“as above, so below”—resonates with Wilber’s insistence that quadrants apply at every scale. In this sense, Integral Theory is not a radical break from older Western metaphysics but a modernization, recast in psychological and systemic language.

Other comparisons reveal what Integral Theory overlooks. Shamanic and indigenous cosmologies often describe reality not as a ladder but as a web: upper, middle, and lower worlds interwoven, or cycles of renewal tied to the land and ancestors. These do not fit easily into AQAL’s linear hierarchy. Similarly, Christian mysticism emphasizes relational love and union with God, which sit awkwardly in a model that privileges impersonal non-duality. Taoism emphasizes balance of yin and yang, flow and return, rather than ascent through stages. In each case, Wilber’s framework can translate these into quadrants and lines, but the translation sometimes distorts. What emerges is not the tradition itself but an Integralized version of it, fitted to the AQAL grid.

The cross-mapping reveals both the brilliance and the bias of Integral Theory. Its brilliance lies in its ability to take scattered insights—Theosophical planes, Spiral Dynamics, Buddhist meditation states, developmental psychology—and weave them into one tapestry. Its bias lies in the fact that it privileges hierarchical, stage-based, evolutionary frameworks while flattening cyclical, relational, or non-linear ones. It is inclusive, but selectively so. It integrates, but on its own terms.

In the end, Integral Theory’s cross-mapping shows its true nature: not a discovery of a universal structure but a synthesis of favored traditions rebranded into a modern meta-framework. It is a mirror of its sources, refracted through Wilber’s vision. That does not erase its value; it only reminds us that “integral” is never neutral. Every inclusion is also a translation, and every translation reshapes the original.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Contemporary Relevance

Integral Theory may have peaked in cultural visibility in the 1990s and early 2000s, but it has not vanished. Its vocabulary—quadrants, levels, states, lines—still circulates in spiritual circles, coaching programs, leadership seminars, and academic discussions of consciousness. What began as Wilber’s personal synthesis has evolved into a loose movement, a community of practitioners and thinkers who continue to apply AQAL as both philosophy and praxis. Its endurance is a sign that it fills a void: the hunger for a framework that honors complexity without dissolving into chaos.

In spiritual practice, Integral Theory offers modern seekers a bridge between traditional meditation and contemporary psychology. Practices like “Integral Life Practice” weave together meditation, shadow work, physical training, and service, claiming to cultivate all dimensions of the self rather than just one. The relevance here is in integration: seekers are no longer forced to choose between therapy and meditation, science and spirituality. AQAL provides a framework in which all of these can coexist, each mapped to a quadrant or line, each honored as necessary. For practitioners burned out on dogmatic religion or shallow New Age eclecticism, the Integral approach offers both structure and inclusivity.

In coaching and leadership, Integral Theory has found a surprising foothold. Organizational consultants use the quadrants to analyze businesses, showing how individual behavior, company culture, systemic structures, and personal mindsets all interlock. Leadership programs emphasize developmental stages, encouraging leaders to move beyond egoic or ethnocentric perspectives toward worldcentric, integrative vision. In education, AQAL has been applied to curricula that balance cognitive, emotional, and moral development, aiming to produce not just skilled workers but whole human beings. The model’s relevance here lies in its practicality: it provides a multi-dimensional lens that can reveal blind spots in institutions and inspire more holistic design.

In psychology and therapy, AQAL’s influence is subtler but real. Transpersonal psychology, integral psychotherapy, and certain forms of trauma therapy have adopted aspects of the framework, especially its emphasis on lines of development and states of consciousness. Clients are encouraged to see their growth not as linear but as multi-faceted, with strengths and shadows across multiple domains. Integral theory validates mystical or altered states while grounding them in developmental psychology, giving therapists language to hold both the ordinary and the extraordinary without pathologizing one or dismissing the other.

Even in cultural analysis, Wilber’s framework continues to resonate. His idea that modern conflicts are developmental clashes—traditionalist vs. modernist vs. postmodernist worldviews—still echoes in political discourse. Many integrally-informed writers argue that polarization is not merely ideological but developmental: different levels of consciousness locked in struggle. Whether or not one accepts this framing, it remains a provocative lens for interpreting social dynamics.

The relevance of Integral Theory today lies less in its claim to be a “theory of everything” and more in its utility as a meta-framework. It provides a language to talk about complexity in a time when complexity overwhelms. It reassures seekers that no perspective needs to be discarded, only contextualized. It encourages practitioners to see themselves not as fragments—body here, mind there, spirit somewhere else—but as multi-layered beings capable of growth in all dimensions.

Yet its relevance is also contested. Some find the model too abstract, too intellectual, too tied to Wilber himself. Others see it as dated, a relic of a time when grand unifying theories were fashionable. Still, for those who resonate with it, Integral Theory remains a compass. It may not be the final word, but it continues to function as orientation—a reminder that life is not flat but layered, not singular but plural, not chaotic but patterned. In this sense, its contemporary relevance is modest but enduring: a framework that refuses reductionism and insists, even now, that integration is possible.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Closing

Integral Theory stands as one of the most ambitious intellectual projects of the modern era. At a time when fragmentation defined every field—psychology, philosophy, religion, politics—Ken Wilber dared to sketch a framework that claimed to hold it all together. The AQAL model is both audacious and alluring: it insists that every perspective has value, that no truth is partial when seen in context, that consciousness itself evolves through discernible stages. It is a philosophy of integration in a world addicted to division. That is its enduring strength.

What Integral Theory is, above all, is a meta-framework. It does not replace psychology, sociology, or spirituality; it situates them. It is not a religion, though it validates mystical experience. It is not a science, though it draws from developmental psychology and systems theory. It is scaffolding: a structure in which diverse truths can be held without collapsing into relativism. For practitioners, its power lies in orientation. It helps people locate themselves, their cultures, their practices, within a larger map that honors complexity without surrendering to chaos. It reminds us that growth is real, that perspectives evolve, and that integration is possible.

But what Integral Theory isn’t is a final revelation or flawless science. Its grid is elegant, but elegance is not proof. Its developmental sequences are plausible, but human life is often messier than staged ladders suggest. Its inclusivity is genuine, but selective—privileging certain traditions, particularly Eastern non-dualism, while translating or flattening others. And its authority is fragile: tied to one man’s synthesis, dependent on developmental psychology that is itself contested, too abstract at times to translate into daily life.

In the end, Integral Theory is best understood as a mirror of its cultural moment. It reflects the late twentieth century’s hunger for coherence, its obsession with systems, its reverence for both science and spirituality. It is not the “theory of everything” it sometimes claims to be, but it is a remarkable attempt to hold everything in view. Its value lies not in being ultimate truth but in being a tool: a way of thinking integrally, a lens that trains the mind to see wholeness where it would otherwise see fragments.

To use Integral Theory wisely is to treat it as scaffolding. It can orient, but it cannot confine. It can suggest pathways, but it cannot dictate reality. It can inspire integration, but it cannot force it. What it offers is an invitation: to think bigger, to honor complexity, to grow beyond narrow perspectives. That invitation, even now, remains powerful. And perhaps that is the most integral lesson of all: no map is final, but some maps help us see more of the territory—and that, in a fractured age, is gift enough.

Leave a comment