꩜ Origins & Historical Roots

Theosophy as a movement was born in the late nineteenth century, at a moment when industrial modernity was colliding with a sudden flood of Eastern texts and philosophies into the West. Its central architect was Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, a Russian mystic who positioned herself as both revealer and compiler of an ancient “wisdom tradition” that she claimed underlay all world religions. With the publication of Isis Unveiled in 1877 and The Secret Doctrine in 1888, she laid out a sweeping vision: reality is structured by invisible laws, humanity evolves through hidden stages of development, and truth is not confined to church dogma but exists as a perennial stream accessible to initiates. To carry this work forward, the Theosophical Society was founded in New York in 1875, later relocating its headquarters to Adyar, India. From the beginning, the goal was ambitious—nothing less than the synthesis of science, philosophy, and religion into one coherent framework that could chart the invisible world.

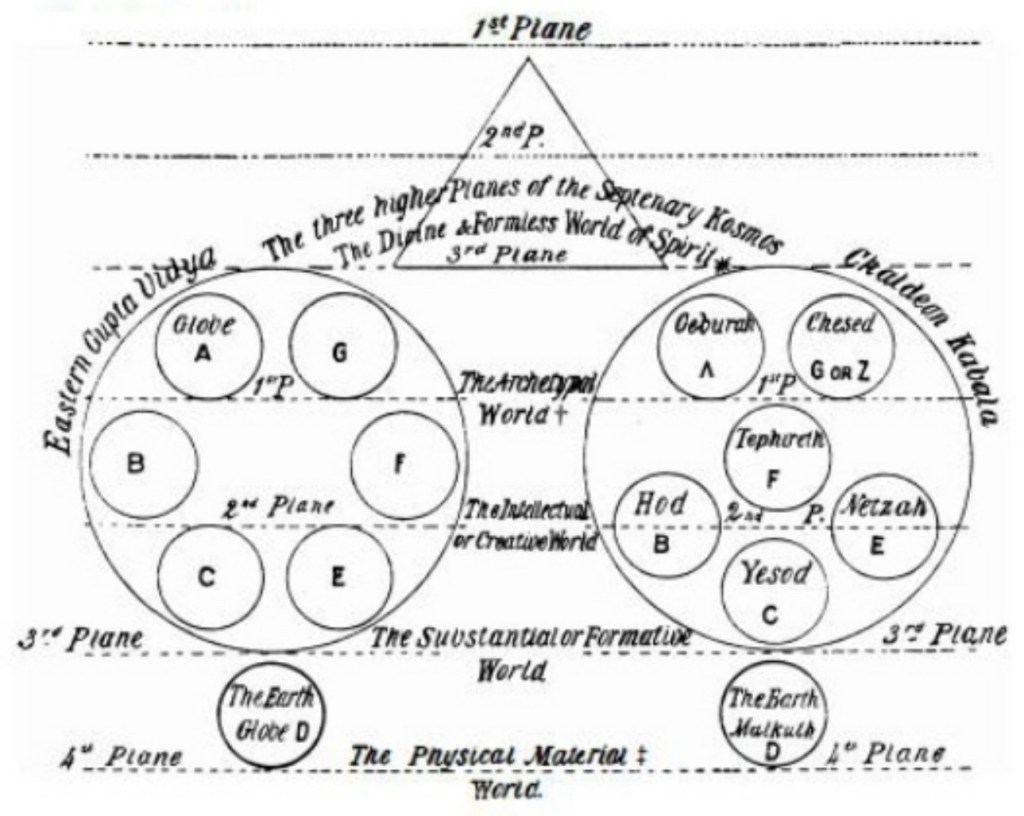

Comparative diagram aligning Theosophy’s seven planes with the Kabbalistic Four Worlds. Early-20th-century Theosophical illustration showing correspondences between Eastern Gupta-Vidya and the Chaldean Kabbalah. Public domain / Theosophical Society archives.

Theosophy did not arise in a vacuum. Its “planes of existence” drew heavily on earlier traditions, sometimes faithfully, sometimes distorted through Victorian eyes. From Hinduism it borrowed the concepts of lokas (cosmic realms), koshas (sheaths of being), and tattvas (fundamental elements of reality), reframing them into a ladder of subtle planes stacked above the physical. From Buddhism it adopted ideas of layered consciousness, subtle post-mortem states, and the shifting continuity of self, which blended into what would become the “astral” and “mental” planes. From Western esotericism—particularly Neoplatonism and Hermeticism—it absorbed the ancient “Great Chain of Being” and the notion of ascent through successive layers of reality. Even contemporary science and occult experiments left their imprint: nineteenth-century fascination with magnetism, mesmerism, and psychic research gave the Theosophists a vocabulary of “subtle matter” and “energetic bodies,” which they then slotted into their metaphysical framework. The resulting picture was a composite: not a recovered revelation, but an esoteric bricolage translated into Victorian metaphysics.

Blavatsky set the stage, but it was her successors who solidified the planes of existence into the familiar seven-fold scheme. Charles Webster Leadbeater, a former Anglican priest turned clairvoyant, claimed to directly perceive these planes with his inner vision. His detailed reports, later compiled with Annie Besant, became the backbone of Theosophy’s technical cosmology. They described not only the seven major planes but also their subdivisions, mapping out forty-nine distinct levels of being. For them, this was not speculation but observation—clairvoyance treated as a kind of spiritual microscopy. Through their writings, the seven planes model became standard doctrine, spreading outward into occult lodges, esoteric schools, and eventually New Age thought.

Diagram of the Seven Planes of Existence, showing the ascent from the Physical through the Astral, Mental, Buddhic, and higher cosmic planes. Adapted from C. W. Leadbeater’s A Textbook of Theosophy (1912) and The Chakras (1927). Public domain / Theosophical Society archives.

The intention behind the system was fourfold. First, to systematize the unseen—to show that invisible reality had as much order and law as the physical sciences were uncovering in matter. Second, to merge science with mysticism, presenting these planes as structured “dimensions” rather than vague heavens. Third, to anchor morality in cosmology, teaching that human choices shaped which plane one resonated with and thus determined one’s evolutionary progress. And fourth, to universalize spirituality by claiming all traditions were fragments of this single ladder, refracted through different cultural lenses but pointing to the same hierarchy of ascent.

Theosophy, however, was not without its flaws. It often presented itself as the recovery of “ancient wisdom,” but in reality it was a synthesis stitched together from Hindu, Buddhist, and Hermetic ideas, filtered through the worldview of nineteenth-century Europeans. Its scientific posture was more rhetorical than empirical, relying on the unverifiable clairvoyant claims of Leadbeater and Besant. And, like much of the Orientalism of its time, it appropriated Eastern language while bending it to Western frameworks, sometimes distorting the original intent. Still, despite these shortcomings, Theosophy succeeded in something remarkable: it provided a clear, imaginative architecture for the unseen. More than a century later, when people in the West speak of “astral planes” or “subtle bodies,” they are usually drawing—knowingly or not—from this Theosophical inheritance.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ The Structure and Function of the Planes

The Theosophical system lays out seven planes of existence, each conceived not as a separate world floating in space but as an interpenetrating state of reality, finer or coarser according to its vibration. The claim was that just as matter exists in states—solid, liquid, gas, plasma—so too does consciousness inhabit states that grade from the dense physical to the purely spiritual. Each plane is both an environment and a vehicle: a domain of life in which activity unfolds, and a sheath or body through which that activity is expressed. To understand the planes, then, is to understand the anatomy of existence itself, both cosmic and human.

The most immediate is the Physical Plane, the bedrock of incarnation. It is not simply the visible world of bones, blood, and stone but also its unseen etheric foundation, a subtle lattice that channels vitality and orders form. The physical stabilizes; it anchors the soul into time, space, and gravity. Without it, consciousness would drift. With it, we are granted a stage on which experience can play out in coherent sequence. The dense body persists because the etheric body constantly feeds and repairs it, functioning like a template of energy beneath matter’s weight. Thus the physical is not dead matter but the living root of embodiment, the first gate into manifestation.

Beyond this is the Astral Plane, the realm of desire, imagination, and emotional energy. Theosophy cast it not as fantasy but as a real field in which feelings acquire substance. Every passion, fear, or longing becomes a magnetic current, shaping landscapes of dream and vision. Its function is propulsion: the astral moves us, drives us toward or away, colors every perception with attraction or repulsion. It is both the engine of creativity and the theater of illusion. In this sense, the astral is dangerous and indispensable—it fuels the drama of human life, yet it also distorts and deceives, cloaking clarity in glamour.

The Mental Plane rises above it as the workshop of thought. Here consciousness learns to structure, categorize, and render the chaos of impressions into intelligible form. Theosophy divided it into two halves: the lower mental, which handles concrete ideas, language, and logical construction, and the higher mental, which contemplates archetypes, ideals, and pure abstractions. The mental functions as translator. It builds concepts, projects meaning, and generates the thought-forms that populate the subtle world. Every idea is a form; every thought has objective existence here. The mental plane thus organizes both the inner life of reasoning and the outer world of culture, philosophy, and science.

Above the mind lies the Buddhic Plane, the field of direct knowing. If the mental organizes by separation, the Buddhic unifies by identity. It is the plane of intuition, where truth is grasped not by analysis but by recognition—an immediate perception of wholeness. Its function is reconciliation. Here compassion is not an emotion but a way of seeing, the collapse of division between self and other. Contact with the Buddhic reorients the lower planes, harmonizing thought and feeling in the light of unity. For Theosophy, this was the true ground of mysticism: the soul’s awakening to its participation in the living whole.

Still higher is the Atmic Plane, the domain of will. Where the Buddhic dissolves boundaries in love, the Atmic cuts through confusion with decisive purpose. It is the stream of divine volition, the archetypal current that guides evolution and destiny. To act in alignment with the Atmic is to act from the soul’s highest directive rather than from ego or desire. Its function is directive power. Through the Atmic body, the individual becomes a conscious participant in the greater plan of life, capable of transformation and initiation that ripple outward beyond personal scale.

The final two planes stretch toward the unimaginable. The Anupadaka Plane was described as the seat of the Monad, the indivisible spark of divine individuality that persists through all incarnations and dissolutions. Its function is preservation—it safeguards the continuity of the true self even as personalities rise and fall. And the Adi Plane was cast as the ultimate ground, the unconditioned source from which all the others emanate. It has no function in the human sense; it simply is. The Adi is the undivided root, the first differentiation from the Absolute, and therefore the silent backdrop against which the entire drama of existence unfolds.

Together these seven planes form the skeletal and muscular system of Theosophical cosmology. Each has its environment, each has its vehicle, each plays a distinct role: the Physical grounds, the Astral propels, the Mental organizes, the Buddhic reconciles, the Atmic directs, the Anupadaka preserves, and the Adi originates. This is not merely a ladder for mystics but an anatomy of reality itself, meant to explain why life has coherence, why consciousness has layers, and why evolution has a goal. To climb these planes is not to escape the world but to integrate it—learning to live as a being who spans matter and spirit alike.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Human Interaction with the Planes

Theosophy never intended its map to remain abstract. The planes were not distant heavens to be admired but active fields that human beings enter every day, usually without realizing it. The model was meant to explain why dreams feel real, why thoughts ripple outward, why mystics glimpse unity, and why death does not end consciousness but simply transfers it to subtler vehicles. To live, in this system, is to be a multi-layered being constantly shifting attention up and down the spectrum. Awareness narrows to the physical in waking life, but it drifts into the astral when we dream, brushes the mental when we think, and occasionally flashes into the Buddhic when intuition or compassion breaks through. The planes are not elsewhere—they are here, now, interwoven with daily existence.

On the most familiar level, the Physical Plane is where embodiment unfolds. Eating, walking, building, and sensing all depend on the dense body, yet even here interaction is more complex than it appears. The etheric web silently sustains vitality, carrying prana or life-force into tissues, knitting wounds, regulating the nervous system. Fatigue, illness, or sudden vigor are understood as fluctuations in this etheric transmission. Thus every breath and heartbeat is already a dialogue between planes, physical processes grounded in subtler flows.

When consciousness loosens its grip on the body, it drifts into the Astral Plane. This occurs every night in sleep, when dreams mirror our desires, fears, and memories in fluid imagery. Emotions here have substance; anger radiates as a storm, joy shines as light. Psychic impressions and visions are also interpreted as astral perceptions, fleeting openings where sensitivity pierces the veil. In life, we interact with the astral whenever we feel pulled, repelled, enchanted, or deceived. It is the plane of glamour and empathy alike, shaping how we experience not just our own moods but the atmospheres of others.

The Mental Plane is engaged whenever thought takes form. Every calculation, every belief, every creative idea is said to leave a real imprint in mental matter. In daily life, this explains how moods spread, how ideologies take hold, or how a single concept can inspire thousands. Education, philosophy, and culture are mental interactions, training the mind to handle both the concrete and the abstract. For Theosophists, thought was not private; it was broadcast, absorbed, and reinforced across the shared field of the mental plane.

The higher planes are more elusive but not absent. The Buddhic Plane touches ordinary life through flashes of intuition, sudden empathy, or experiences of unity that defy explanation. In those moments when self dissolves—whether in love, in art, in nature, or in mystical vision—the Buddhic field is active. Its presence is rare in daily awareness but unmistakable when it breaks through, leaving an aftertaste of clarity and peace.

Contact with the Atmic Plane is even rarer, yet it manifests in the unmistakable force of true will. Not desire, not ambition, but a clear directive that cuts through hesitation and compels transformation. Mystics described this as alignment with divine purpose, a current of energy that seizes the individual and carries them toward a destiny larger than themselves. On rare occasions, this will has reshaped history through figures who embodied it—teachers, revolutionaries, and initiates who acted with the weight of archetypal authority.

Interaction with the Anupadaka and Adi Planes is almost entirely beyond normal awareness. They are touched only in the highest initiatory states or in the process of death, when the soul sheds body after body and returns to its monadic root. Yet their influence is constant, like gravity: the Monad preserves identity across incarnations, and the Adi remains the silent backdrop of all experience. We do not consciously move within them, but we are never apart from them.

Even death itself is explained as an interaction with the planes. At physical death, the etheric dissolves, but consciousness continues in the astral, where desires are worked through. Later, the mental vehicle sheds as thoughts lose coherence, leaving the soul to rest in the higher layers until a new cycle of incarnation draws it downward again. The process is not an end but a migration, the shifting of awareness from one sheath to another.

In this way, Theosophy framed human life as a constant dialogue with the planes. We are not confined to one world but stretched across seven, using the physical to act, the astral to feel, the mental to think, the Buddhic to know, the Atmic to will, the Anupadaka to persist, and the Adi simply to be. Most people live in partial awareness, flickering between body, feeling, and thought, unaware of the subtler ranges. Yet the task of spiritual practice, in this model, is to awaken to all seven, to learn how to dwell consciously in each, and to integrate them into one coherent being. Thus the planes are not distant abstractions but the anatomy of human experience itself, waiting to be recognized.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Purpose and Esoteric Function

The Theosophical system was never offered as a neutral map. It carried a mission. The planes were presented not merely as descriptions of hidden worlds but as the framework of human evolution, the curriculum of the soul written into the very fabric of reality. To Blavatsky, Leadbeater, Besant, and their successors, the function of the sevenfold ladder was to show humanity its place in a vast design and to provide both explanation and incentive for spiritual development. The planes were not incidental—they were law, structure, destiny.

At its most basic level, the doctrine supplied a moral cosmology. Every thought, feeling, and action was said to vibrate on a corresponding plane, leaving tangible traces that shaped the soul’s trajectory. To indulge destructive emotions meant thickening the astral sheath with turbulence; to cultivate noble thought meant refining the mental body and aligning it with higher archetypes. In this way, ethics were no longer arbitrary codes but the physics of consciousness. Morality was simply hygiene of the subtle bodies, a law as strict as gravity: harmony elevated, disharmony degraded. Spiritual progress was framed as a matter of resonance—living in such a way that the soul vibrated more coherently with the Buddhic and Atmic currents, rather than remaining trapped in the density of astral desire or lower mental fixation.

Beyond morality, the planes functioned as the scaffolding of initiation. The Theosophical Society, echoing older mystery traditions, described spiritual practice as the gradual mastery of successive planes. The aspirant was to discipline the physical, purify the astral, clarify the mental, awaken the Buddhic, and align with the Atmic until finally the Monad could shine unobstructed. Each initiation was said to confer awareness and control of a higher vehicle, enabling the initiate to operate consciously beyond the physical. This ladder of mastery provided the rationale for meditation, asceticism, service, and study: all were tools to train the soul’s instruments for subtler work.

The planes also had a didactic purpose—to reconcile science and religion in a single esoteric framework. At the turn of the twentieth century, physics was unraveling old certainties, while organized religion seemed increasingly hollow to educated seekers. Theosophy positioned the planes as a synthesis: invisible worlds ordered as rigorously as chemistry, yet infused with spiritual meaning. The etheric was explained in terms of vibratory energy, the astral in terms of subtle matter, the mental in terms of archetypal forms. To its adherents, this was proof that spirituality could be scientific, that higher realities could be studied with the same seriousness as any laboratory phenomenon.

Esoterically, the planes served as a cosmic ladder of return. Human beings were not accidental products of evolution but sparks of divinity descending from the Adi through successive veils into the physical, then climbing back upward through cycles of reincarnation. Life was exile and homecoming at once: each incarnation a chance to refine the vehicles, to work off karmic residue, and to reclaim forgotten awareness. The planes thus offered an answer to suffering—pain was the friction of misalignment, ignorance the narrowing of consciousness to a single plane. Redemption lay not in escape but in recognition and integration, a recovery of one’s full spectrum.

For occult workers, the planes functioned as operational fields. Rituals, clairvoyant experiments, and magical practices were all described in terms of manipulating energies across planes. Healing meant adjusting etheric currents; psychic communication meant tuning into astral substance; theurgy meant invoking higher forces through the mental and Buddhic layers. The model gave practitioners a language to classify experiences and to pursue them systematically rather than chaotically.

Ultimately, the esoteric function of the seven planes was to anchor a vision of purposeful cosmos. Reality, in this scheme, is not a chaos of blind forces but a graded order, a schoolhouse in which consciousness is trained. The ladder is both map and mandate: to exist is already to be enrolled, and to awaken is to realize that one is climbing. For its architects, this was the gift of Theosophy—the revelation that every moment of thought, every surge of feeling, every act of will is not lost but inscribed into the structure of the planes, shaping the destiny of the soul and, through it, the unfolding of the universe itself.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Criticisms and Limits

For all its elegance, the Theosophical model of the planes is not beyond question. In fact, its very clarity invites skepticism, because reality—especially consciousness—rarely obeys such neat hierarchies. The ladder may inspire, but it also reveals the fingerprints of the culture and era that produced it. To take it seriously requires also to see its limits.

The first and most obvious critique is over-systematization. Theosophy built its cosmology in sevens because sevens appealed to the occult imagination of the time. Seven colors of the spectrum, seven notes of the scale, seven days of the week—why not seven planes of existence? But this neatness risks being more numerology than discovery. The world of consciousness is messy, recursive, fractal. Experiences of mystics, shamans, and modern explorers of altered states often defy linear ladders. Some collapse into non-duality at once, others spiral through chaotic landscapes, others fragment into networks rather than rising up steps. The rigid sevenfold scheme can obscure the fluidity of lived experience.

Second is the colonial lens. Theosophy claimed to be reviving “ancient wisdom,” but much of what it presented was lifted, rebranded, and often distorted from Hindu and Buddhist sources. Terms like astral and buddhic were not neutral—they were Victorian interpretations of Sanskrit concepts bent to fit Western categories. In the process, nuance was lost. The Buddhist notion of non-self, for example, sits awkwardly inside a model that insists on the eternal Monad. What emerged was less a universal truth than a cultural remix, shaped by Western fascination with the East but filtered through its own biases.

A third weakness is the problem of verification. Leadbeater and Besant claimed clairvoyant vision of the planes down to the details of sub-levels and subtle matter. But these reports cannot be independently confirmed. Unlike a telescope or microscope, clairvoyance does not provide shared, repeatable data. To accept the model requires faith in the authority of its seers. Critics argued that such visions were colored by imagination, expectation, or subconscious projection. Even within Theosophical circles, discrepancies emerged between different accounts of what the higher planes contained. The precision of “forty-nine sub-planes” sounds impressive, but precision without consensus is fragile.

The model also risks hierarchical rigidity. By stacking planes from dense to divine, it can foster the idea that lower levels are inherently inferior and higher levels inherently better. This dualism devalues the physical and emotional aspects of life, casting them as obstacles to be escaped rather than integral facets of being. While Theosophists insisted integration was the goal, in practice the discourse often slipped into elitism, where “higher” equated to purity and “lower” to corruption. Such framing can produce spiritual bypassing—denying the messy realities of human life in pursuit of imagined transcendence.

Another limit is historical obsolescence. Theosophy presented its planes as a “scientific” cosmology, yet its science was rooted in nineteenth-century physics. The ether was assumed to be the medium of subtle forces, and “subtle matter” was described in terms that mirrored contemporary chemistry. Modern science has long since abandoned those frameworks. While quantum physics and field theory may offer analogies, the original Theosophical claims about vibrations and ethers have little standing in today’s empirical context. What remains valuable is symbolic, not literal.

Finally, the model can obscure more than it reveals when treated as absolute. Consciousness is not a ladder but a living field, complex and multi-directional. Theosophy’s planes capture important archetypes—the material body, emotional field, thought structures, unity, will, and source—but they do so in a way that risks flattening the diversity of experience into a single framework. Other traditions, from shamanism to modern depth psychology, offer maps that emphasize cycles, webs, or multiplicities rather than linear ascent. To hold the Theosophical model too tightly is to mistake one cultural diagram for the full anatomy of spirit.

None of this erases the value of the planes. They gave language to the unseen, inspired generations of seekers, and built a bridge between East and West at a time when few such bridges existed. But their authority must be tempered by context: they are a nineteenth-century esoteric artifact, not a final revelation. To use them wisely is to honor both their insight and their limitation, seeing in them not a universal law but one attempt—brilliant, flawed, and human—to chart the unchartable.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

What they are not is a definitive map of reality. They are not proven dimensions, nor the only way to frame subtle experience. They do not replace the complexity of neuroscience, psychology, or lived spiritual traditions. To take them literally as geography risks mistaking myth for science, and to treat them as final risks closing off the very mystery they were meant to honor.

꩜ Cross-Mapping to Other Systems

The seven planes of Theosophy did not emerge in isolation. They were, in many ways, an attempt to stitch together fragments of older cosmologies into a single coherent ladder. Comparing them against other systems reveals both the continuity of human attempts to chart consciousness and the distortions that arise when diverse traditions are compressed into a rigid framework.

In Hindu cosmology, the echoes are unmistakable. The idea of lokas—worlds or realms in which beings dwell—provides a clear precedent. The koshas, or sheaths of the self, also parallel the Theosophical notion of bodies aligned with planes: annamaya (physical), pranamaya (vital), manomaya (mental), vijnanamaya (intellectual), and anandamaya (bliss) map closely onto the physical, astral, mental, and buddhic layers. Theosophy drew freely from these concepts, but its Western architects reframed them in a hierarchical, linear way that often downplayed the cyclical and non-dual emphases of Indian thought. Where Vedanta points toward dissolution of self in Brahman, Theosophy insists on the Monad as enduring individuality.

From Buddhism, particularly Tibetan and Mahayana strands, Theosophy borrowed the idea of subtle post-mortem states and gradations of awareness. The bardo teachings, describing transitional states between death and rebirth, influenced Theosophical accounts of astral and mental after-death journeys. Buddhist cosmology also enumerates multiple realms of existence, from hell realms to god realms, which can be seen as parallels to the astral and higher planes. Yet here too the divergence is stark: Buddhism emphasizes impermanence, no-self, and liberation from the entire ladder of existence, whereas Theosophy posits the eternal Monad climbing upward. The ladder becomes a schoolhouse rather than a trap.

Kabbalah offers another illuminating comparison. The Tree of Life’s ten sefirot and four worlds—Assiah (action/physical), Yetzirah (formation/astral), Briah (creation/mental), Atziluth (emanation/divine)—mirror the physical, astral, mental, and spiritual planes with striking closeness. Both systems imagine interpenetrating worlds where divine energy steps down through successive veils until reaching material form. Yet the Kabbalistic framework is more explicitly relational: the sefirot are dynamic emanations of divine attributes, not static levels of substance. Theosophy’s ladder simplifies this dynamism into a linear progression of ascent.

Even within Western esotericism, the Great Chain of Being of Neoplatonism—Matter, Soul, Intellect, and the One—prefigures Theosophy’s descent from the Adi through successive planes. Renaissance Hermeticism also envisioned subtle bodies and intermediary worlds, the astral light being a key precursor to the Theosophical astral plane. The difference is that Theosophy systematized these fragments with a scientific gloss, translating loose metaphors into diagrams of “sub-planes” and treating mystical ascent as if it were a technical manual.

Modern frameworks echo the pattern in new forms. Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory, for example, explicitly acknowledges its debt to Theosophy. His model of developmental levels—gross, subtle, causal, non-dual—mirrors the physical, astral/mental, buddhic/atmic, and Adi. Likewise, transpersonal psychology often borrows the idea of layered consciousness, using language such as “higher self,” “collective unconscious,” or “superconscious” that resonates with the Theosophical spectrum. In each case, the sevenfold ladder acts as a scaffolding for later attempts to reconcile psychology with spirituality.

At the same time, comparison highlights the limitations of universality. Shamanic cosmologies often describe three worlds—upper, middle, and lower—rather than seven. Taoist models emphasize flows and polarities rather than ladders. Indigenous traditions map consciousness through cycles, directions, or animal powers, not stratified planes. This suggests that while Theosophy captured genuine archetypal themes—matter, emotion, thought, unity, will, and source—its insistence on seven fixed levels is a cultural artifact, not a universal truth.

Cross-mapping therefore shows both convergence and distortion. Theosophy successfully brought together scattered threads into a single tapestry, giving Western seekers a structure to think with. But it also ironed out subtleties, imposed hierarchies, and claimed universality where only partial correspondence existed. The value of the comparison lies in balance: to see the Theosophical planes not as the final map but as one iteration of a deeper human impulse—the need to chart the invisible, to find order in consciousness, and to tell ourselves where we stand in the great unfolding of spirit.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Contemporary Relevance

The Theosophical planes may have been codified in the nineteenth century, but they have never really left the conversation. Their language—astral, mental, buddhic—slipped into the bloodstream of Western spirituality so completely that many who use these terms today have no idea of their origin. New Age books speak casually of astral projection; psychics describe mental impressions; healers refer to etheric bodies. All of this traces back, directly or indirectly, to the scaffolding laid down by Theosophy. It provided a vocabulary that proved durable, not because it was universally true, but because it was vivid, portable, and adaptable.

In contemporary spiritual practice, the planes still serve as a symbolic framework for experience. People who explore meditation, lucid dreaming, psychedelic states, or energy work often need language to describe what they encounter. Theosophy’s planes provide a ready-made map. Dreams feel astral, intellectual clarity feels mental, flashes of unity feel buddhic. Even if the map is simplistic, it helps orient experience and prevents it from being dismissed as meaningless. It functions less as a literal geography and more as an archetypal set of categories through which subtle states can be recognized.

The model also continues to shape esoteric schools and New Age subcultures. Many teachings of modern occult groups, energy healers, and metaphysical writers are essentially Theosophy in new clothing. The seven chakras, popularized in the West around the same period, were easily mapped onto the seven planes, and the two systems became entwined. Workshop leaders speak of clearing the astral, aligning the mental, accessing the higher self—all echoes of the old ladder. The language persists because it is flexible: one can graft crystals, astrology, or modern psychology onto it without much strain.

Yet its relevance is not only symbolic. Theosophy’s planes address a psychological hunger that persists today: the need to see consciousness as layered, meaningful, and evolving. Modern life flattens reality into material surfaces; neuroscience reduces mind to brain chemistry; consumer culture trivializes spirituality into wellness trends. Against this backdrop, the idea of interpenetrating planes offers depth. It affirms that thought, emotion, intuition, and will are not just functions of matter but participants in a larger, structured cosmos. Whether taken literally or metaphorically, the system reassures seekers that their inner experiences have place and purpose.

At the same time, the model has been reinterpreted. Few contemporary thinkers cling to it as a literal scientific cosmology; rather, it is used as a mythic map. The astral is read as the emotional unconscious, the mental as cognitive frameworks, the buddhic as transpersonal empathy, the atmic as alignment with core purpose. In this sense, the planes survive as archetypes of human development. They are not alternative universes but dimensions of self, each with its own integrity and demands.

The danger is that the old hierarchy can still be misused, leading to spiritual elitism or escapism. But the opportunity is to see it as a tool for integration rather than escape. When approached flexibly, the planes remind us that life is multi-layered: we eat and sleep, we feel and dream, we think and plan, we intuit and act. Each layer is real. To live fully is not to flee the lower for the higher but to harmonize them into a coherent whole.

For seekers today, then, the Theosophical planes remain relevant less as dogma than as orientation. They are part of the living archive of humanity’s attempts to map the invisible. They can be used critically, symbolically, or even poetically, without pretending they are final truth. Their persistence proves one thing above all: the hunger for maps of consciousness has not diminished. We still crave a structure that says our experiences matter, that the inner worlds are not illusions but dimensions of being. In that sense, the seven planes endure—not as an ultimate revelation, but as one of the more influential myths of modern spirituality, a bridge between past esotericism and present quests for depth.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ ✦ ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

꩜ Closing

The Theosophical doctrine of the seven planes stands as one of the most influential attempts in modern history to chart the unseen. Its endurance is not proof of its literal truth, but of its imaginative power. By layering existence into ascending states—from dense physical matter through emotion, thought, intuition, will, individuality, and finally source—it offered a coherent scaffold for understanding both the cosmos and the soul. It is orderly, vivid, and accessible enough that generations of seekers have used it as their default map of spirituality. In that sense, it is a landmark achievement: a system that stitched together Eastern metaphysics, Western esotericism, and Victorian science into a single picture that could satisfy the longing for depth in an increasingly materialist age.

But the model’s strength is also its weakness. It is not a universal revelation but a cultural construction, shaped by the imaginations and biases of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century occultists. Its precision—forty-nine subplanes, sevenfold correspondences, clairvoyant schematics—gives the impression of scientific rigor, yet its foundations rest on unverifiable claims. Its hierarchy reflects Western preferences for order, ascent, and individuality, rather than the cyclical, relational, or non-dual frameworks found in the very traditions it borrowed from. And by presenting itself as “ancient wisdom,” Theosophy often obscured the fact that it was a novel synthesis, not a direct transmission.

What the seven planes are, then, is a symbolic ladder of consciousness. They are categories through which to interpret the variety of human experience: the grounding of embodiment, the propulsion of desire, the organization of thought, the reconciliation of intuition, the directive of will, the persistence of essence, and the silence of source. They provide a language that still helps seekers articulate what they feel in dreams, visions, or mystical states. They invite integration—reminding us that life is not flat, but layered, and that growth requires harmonizing those layers rather than escaping them.

In the end, the value of the Theosophical planes lies in their use, not their authority. They are one of many maps humanity has drawn to orient itself in the invisible. They are scaffolding, not foundation; metaphor, not measurement. Used rigidly, they mislead. Used flexibly, they guide. They remind us that we are layered beings, stretched between matter and spirit, and that our work is not to flee the lower for the higher but to inhabit all planes consciously, coherently, and with integrity. That is their enduring gift: not a final word on truth, but a lens through which truth may still be glimpsed.

Leave a comment